Media and Social Media Responses to the 2025 Myanmar Earthquake

The 7.7-magnitude earthquake that struck central Myanmar on March 28, 2025, has not only resulted in the loss of thousands of lives and the destruction of entire towns but also triggered a parallel information crisis—one that has played out across local and international media, social media platforms, and diplomatic channels. The disaster has exposed not only infrastructural vulnerability but also profound fractures in Myanmar’s political, humanitarian, and information systems. From highly curated state narratives to independent investigative journalism and unfiltered, often chaotic citizen reporting online, the earthquake’s aftermath reveals a country struggling not just with seismic shifts beneath its feet, but with collapsing structures of governance, accountability, and public trust.

Initial reports from international media were quick to highlight the scale of the devastation. Reuters confirmed the death toll had surpassed 3,400, with thousands injured and displaced, and noted that the combination of unseasonal rains and high temperatures was complicating rescue and medical efforts. The Guardian focused on how the earthquake exacerbated the already-precarious conditions faced by millions due to years of civil war and military repression. It emphasized how critical infrastructure such as hospitals, schools, and government offices were either destroyed or rendered unusable, worsening the plight of an already embattled population. The Associated Press and The New York Post called attention to the absence of U.S. disaster response teams, formerly a standard presence in global emergencies, citing the recent dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) rapid response capabilities. Meanwhile, the United Nations issued an urgent call for humanitarian aid, noting that the earthquake affected more than 17 million people and left thousands of buildings in ruins.

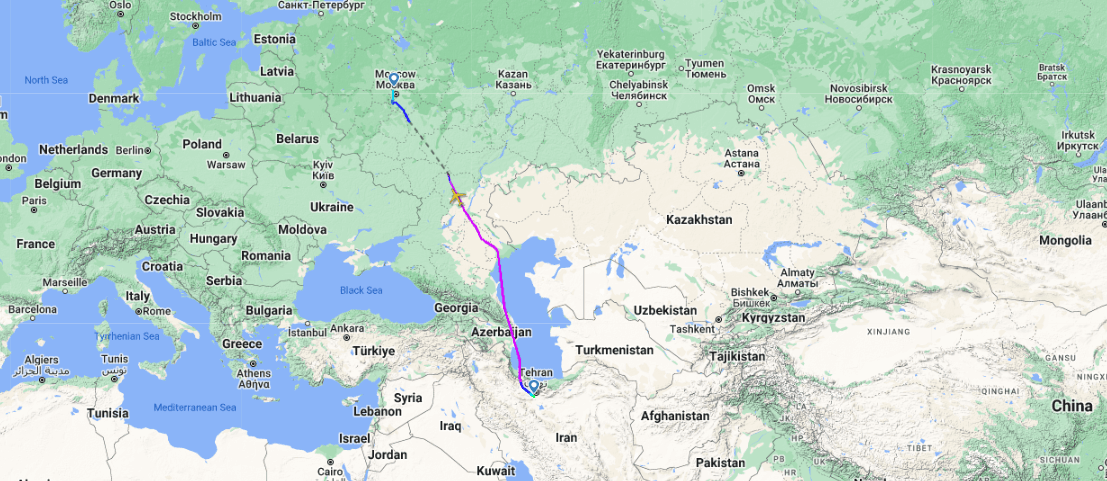

Beyond the factual coverage, more analytical reporting from Chatham House provided a deeper geopolitical and sociopolitical context. The scenes from central Myanmar, they noted, were “apocalyptic.” The destruction of key national infrastructure, including the Ava railway bridge between Mandalay and Sagaing, and Naypyidaw’s international airport, served as a stark reminder of years of poor construction and maintenance under the military regime. According to Chatham House, the earthquake hit hardest in areas most firmly under junta control—a fact that is geographically and symbolically significant. These regions, centered along the Sagaing Fault and the Ayeyarwady River, represent the heartland of the Bamar ethnic majority from which the military draws most of its rank and file. Chatham House also contextualized the disaster as just the latest in a series of national traumas—from the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya in 2017 to the 2021 coup and the ongoing civil war that has fractured the country, leaving only 21 percent of Myanmar firmly in military hands according to ACLED’s November 2024 estimates.

While traditional media provided structured overviews, the role of social media platforms—particularly X (formerly Twitter)—in shaping public understanding and fueling political discourse became undeniable.

State-linked accounts attempted to control the narrative. China Daily posted a polished update featuring the arrival of a fifth shipment of Chinese earthquake relief supplies at Yangon International Airport. Their post included tightly packed crates marked “China Aid for Shared Future,” and detailed the delivery of refined oil, prefabricated housing units, medicines, and vaccines. The optics were carefully curated to showcase China’s solidarity with Myanmar and, by extension, its political alignment with the military regime.

But as Chatham House cautioned, these operations—though highly visible—were often more performative than practical, with many aimed at securing diplomatic capital rather than ensuring broad-based humanitarian access.

In sharp contrast, UN Special Rapporteur Tom Andrews posted a stern warning. His statement on X noted that military attacks were still ongoing in quake-ravaged areas, even as the UN Security Council welcomed the junta’s announcement of a ceasefire. “It is time for a UNSC resolution demanding that all military operations stop and obstructions to the delivery of aid be lifted immediately,” Andrews wrote. His post not only questioned the sincerity of the ceasefire but highlighted the strategic obstruction of aid, which has long been a tactic used by the Myanmar military to control populations and punish opposition-held regions.

Among civilians, outrage and despair poured forth in equally candid terms. One post that quickly went viral read: “Ceasefire? They still bombing and killing. Most of the earthquake aids goes to NGO and Junta Bombing Budget instead of going to the victims of earthquake. Myanmar people only helping its own.”

The statement, raw and emotionally charged, reflects a widespread belief among citizens that international aid is being misused or misdirected—absorbed into military budgets or diverted for propaganda purposes. It also underscores a deep mistrust of both external actors and formal aid organizations perceived as being too willing to engage with the junta. This sentiment aligns with Chatham House’s observation that the regime is likely to co-opt all aid efforts, using them as tools of internal and external legitimacy, and attempting to reframe humanitarian support as the regime’s own initiative.

Local independent media outlets, operating under heavy restrictions, have worked tirelessly to counter this narrative. Myanmar Now, Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), Khit Thit Media, Mizzima News, and The Irrawaddy have all provided critical, ground-level updates despite censorship and threats of detention. These outlets have documented the destruction in specific towns, detailed casualty reports, and traced the breakdown of cultural infrastructure and religious sites. Their reporting offers an invaluable counterpoint to both the regime’s state-run broadcasts and the international media’s high-level overviews, filling in the complex, human details of how the disaster is affecting ordinary people.

The spread of misinformation has further complicated the post-disaster landscape. With internet access disrupted by the military in several areas, families remain disconnected, and communities struggle to organize basic rescue efforts. At the same time, AI-generated images and videos purporting to show earthquake damage have gone viral online. Some feature dramatic but fabricated footage of collapsing skyscrapers or tsunami-like floods, none of which occurred in this event. Fact-checking groups like AFP Fact Check, India Today, and Logically Facts have worked to debunk this content, but the damage to public understanding is already evident. These synthetic media clips, though false, gain traction by feeding into existing anxieties and frustrations about government opacity and international indifference.

In the broader view, the earthquake has become a mirror reflecting all of Myanmar’s deepest fractures: political, ethnic, technological, and infrastructural. It has shown how disasters in the digital age are as much about narrative control as they are about emergency logistics. The global spotlight flickers between immediate tragedy and long-standing injustice, while the people on the ground are left to sort through rubble, not just of buildings, but of trust, governance, and identity.

The media battle surrounding the Myanmar earthquake reveals how deeply contested reality has become in a country defined by civil war and authoritarian rule. Between international headlines, local resistance reporting, social media firestorms, and state-sponsored spin, one thing remains clear: the people of Myanmar are not just struggling to survive a natural disaster—they are also struggling to reclaim the right to tell their own story. And in that battle, every tweet, every photograph, every thread of digital evidence carries weight far beyond the screen.

More from the author